Panama Canal restrictions are already forcing ships to take multi-week detours via the Suez Canal and Cape of Good Hope. One shipping segment is more exposed to these reroutings than any other: specialized tankers that carry liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) from the U.S. to Asia.

America is the world’s largest exporter of LPG, i.e., propane and butane. Since the Neopanamax locks opened in 2016, the vast majority of U.S. LPG exports to Asia have been loaded on very large gas carriers (VLGCs) and sent through the Panama Canal. (VLGCs were too large to fit in the older Panamax locks.)

Canal congestion has arisen periodically over the years, but today’s situation — involving an extreme drought — is different and could cause a lasting shift in VLGC flows away from Panama, according to Oystein Kalleklev, CEO of Avance Gas (Oslo: AGAS).

“We usually see congestion more or less every year in the fourth quarter. Now we’re already seeing it in August,” said Kalleklev during a conference call on Wednesday.

“Of course, the rainfall will come back, but with the congestion, [VLGC] traffic will go up in Q4, so we don’t see any improvement near-term. I think we’ll see a clogged canal for the rest of Q3 and into Q4 and it will probably taper off sometime next year.”

Congestion at canal to persist

“There is also the discussion about climate change and whether the canal is more vulnerable in the future. A lot of people are making that argument,” he said.

Meanwhile, the volume of LPG transported from the U.S. to Asia is expected to continue rising in line with increased U.S. production, creating even more demand for canal transit slots. U.S. LPG exports in January-August rose 10% year on year.

“This trade is expanding,” said Kalleklev, who noted that “America is also expanding a lot on the LNG side.” Liquefied natural gas carriers compete with LPG carriers for Neopanamax transit slots.

“It’s not really any surprise that the canal has been clogging up pretty much every Q4 for the last couple of years, because when they first expanded the canal, it was done to facilitate bigger container ships and all the trade from China to America. Nobody was thinking at that time that America would become the biggest LNG and LPG exporter in the world. The canal was never scaled to this kind of trade — and on top of that, we now have this very big drought.”

If the Neopanamax locks cannot handle all the container ships, LNG ships, passenger ships and LPG ships that want to transit, it’s the LPG ships that get stuck at the back of the queue, said Kallaklev.

“There is precedence given to cruise ships, container ships and LNG ships that have more valuable cargo than LPG ships. So, you will probably see fewer VLGCs transiting through Panama going forward than in the past.”

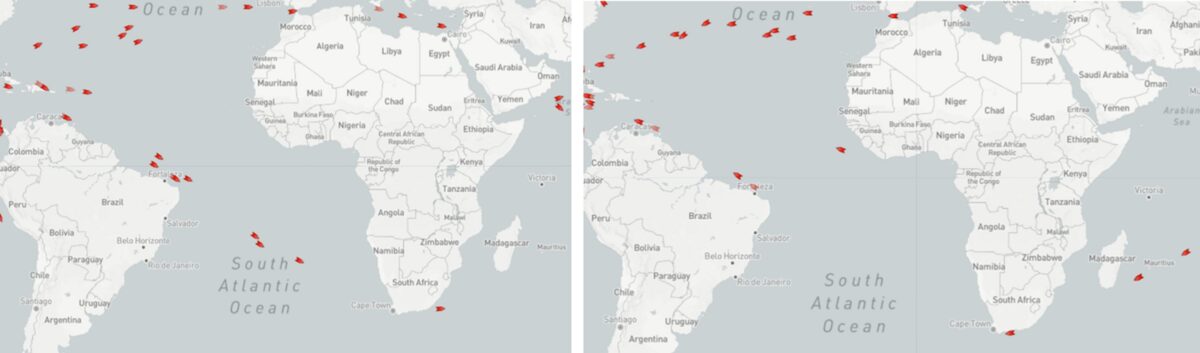

How canal uncertainty affects LPG ship routing

A U.S.-China VLGC voyage takes 58 days round trip via the Panama Canal, 81 days via the Suez Canal and 88 days around the Cape of Good Hope, according to Avance.

The trade is heavily focused on spot deals. After a VLGC unloads in Asia, the shipowner seeks to lock in the next deal as the vessel returns empty, i.e., “in ballast.” If an employment agreement (a “fixture”) is reached, it will include a “laycan” — a period of time when the ship must be available to pick up the cargo.

The problem for VLGCs heading back to the U.S. is that Panama Canal waiting time is now extremely volatile, making laycans more difficult to hit, and spot rates are very high, adding urgency to maintaining schedules.

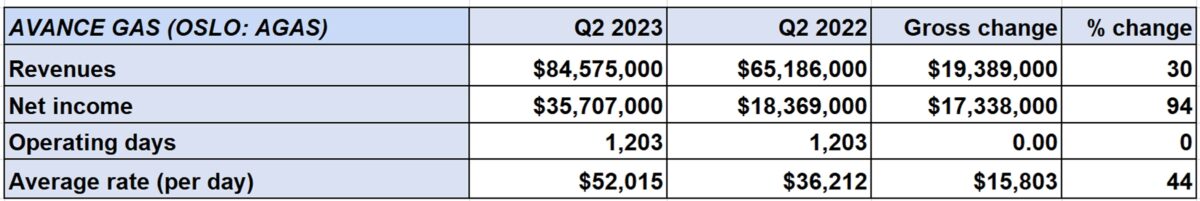

Spot rates are heavily driven by arbitrage: the difference between the price of LPG where it’s produced, in the U.S., and where it’s sold, in Asia. “As of today, LPG is super-cheap in the U.S., driven by very high inventory levels … while demand is strong in Asia,” said Kalleklev.

The price of LPG is currently $275 per ton more expensive in Asia than in the U.S. The transport cost is $175 per ton. That leaves $100 per ton. The average VLGC holds 45,000 tons, equating to a profit of $4.5 million on a single voyage.

“It’s immensely profitable to move our cargo from the U.S. to Asia — and that means you can also pay higher freight,” said Kalleklev.

Leave a reply