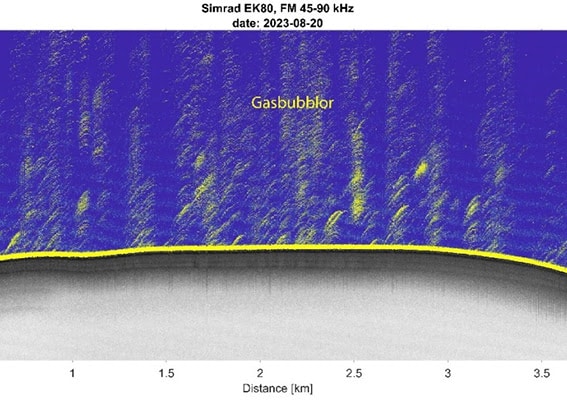

“We know that methane gas can bubble out from shallow coastal seabeds in the Baltic Sea, but I have never seen such an intense bubble release before and definitely not from such a deep area,” says Christian Stranne.

The research project, funded by the Carl Trygger Foundation, aims to expand knowledge about methane and its sources and sinks in the oxygen-free environments in the deeper parts of the Baltic Sea. The project is led by Marcelo Ketzer, professor of environmental science at Linnaeus University.

“Knowledge about the factors that control how much methane is produced in these deeper areas and where the methane goes is limited. How does the system react to, for example, eutrophication or a warmer climate? I knew from one of my previous projects that the methane levels in the sediments in this area are higher than elsewhere in the Baltic Sea, but I never expected methane to bubble out into the sea in this way,” says Marcelo Ketzer.

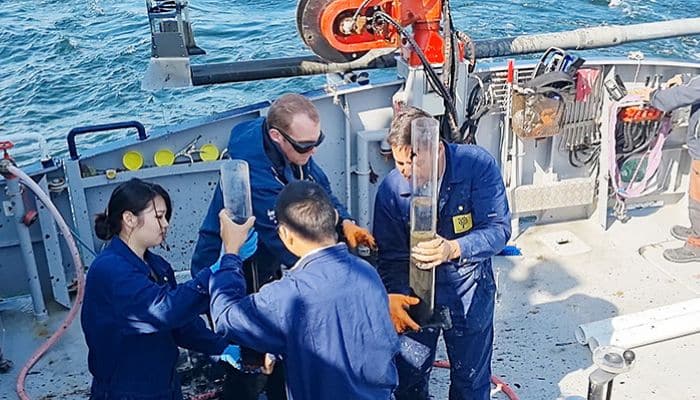

The researchers determined the area’s extent to be about 20 square kilometres (equivalent to almost 4,000 football pitches) and it lies at a depth of around 400 metres. During the expedition, a large number of sediment cores and water samples were collected, and now the researchers hope that further analyses will be able to provide answers to why so much methane gas is released from this specific area.

“We already have a pretty good idea of why it looks the way it does. The size of the sediment grains in the area and the form of the seafloorgive us an indication. It seems like deep ocean currents are causing sediments to accumulate in this particular area, but we need to do more detailed analyses before we can say anything definitive,” says Marcelo Ketzer.

Another interesting discovery made during the expedition concerns how high up through the water column the methane bubbles rise.

“At the depths we are working with here, you can expect the methane bubbles to reach at most perhaps 150-200 metres from the seabed. The methane in the bubbles dissolves in the ocean and therefore they usually gradually decrease in size as they rise towards the sea surface. It is actually quite a complicated balance between pressure effects and diffusion of gases that together determine how size and gas composition develop in a bubble, but the net effect for smaller bubbles is that they lose both size and rise velocity with increased distance from the bottom,” says Christian Stranne.

To the researchers’ great surprise, they could see some bubbles rising to 370 metres from the ocean floor.

Oxygen-free bottoms mighty be the explanation

The researchers have so far not been able to find out exactly how high the bubbles reach. From the sonar, they can see bubbles to at least 40 metres from the sea surface, but it may well be that some bubbles reach significantly higher than that. One of the explanations may be that the bubbles are unusually large, but the researchers have an alternative explanation that they consider more likely.

“Rather, we believe that it is linked to the oxygen-free conditions in the deep water of the Baltic Sea. If there is no oxygen, the levels of dissolved methane in the ocean can be relatively high, which in turn leads to the bubbles not losing methane as quickly.

The bubbles are thus kept more intact in this environment, which means that methane transport towards the sea surface becomes more efficient. It is a hypothesis that we are currently investigating and if it proves to be correct, it could have consequences – if the oxygen conditions in the Baltic Sea deteriorate further, it would probably lead to a greater transport of methane from the deeper parts of the Baltic Sea, but it remains to be investigated how much may leak into the atmosphere,” says Christian Stranne.

“Now we know what to look for and we look forward to testing this model in other areas of the Baltic Sea with similar geological conditions. There are potentially another half dozen places to explore,” Marcelo Ketzer adds.

Leave a reply